Many of us think about the winter solstice merely as the shortest day of the year, but in Chinese culture it is a very important festival. Dongzhi (冬至), which literally translates to “the extreme of winter,” has its theoretical underpinning in the concept of yin yang (陰陽 / 阴阳). It is both a celebration of the shortest day of the year and the return of longer daylight in the weeks ahead. Note that dong zhi is the Mandarin pronunciation; in Cantonese, it is dong zee.

During winter solstice, families gather together to make and eat tang yuan (湯圓 / 汤圆) for dongzhi. (Tang yuan, which is how it’s most commonly spelled in English, is based on the Mandarin pronunciation; in Cantonese, it is tong yoon.) Tang yuan are small circular dumplings made with glutinous rice flour and water. The circular shape of the dumplings symbolizes one’s family coming together (or tuanyuan, 團圓 / 团圆). Some families make the sweet version of tang yuan. However, in Toisan (台山), where my family is from, people often cook tang yuan in a savory broth with seafood, vegetables, and meat.

Mama Lin typically prepares a broth that is flavored with chicken stock, dried shrimp, Chinese sausage, shallots/onions, and sometimes lean pork. To serve, she’ll top the bowl of tang yuan with cooked daikon, fried fish cake, scallions, and cilantro. It is the ultimate winter comfort food!

By the way, most traditional Chinese holidays are based on the lunar calendar. As a result, Chinese winter solstice celebrations may be on the same day or a day later than winter solstice based on the Gregorian calendar.

SAVORY TANG YUAN COOKING NOTES

USING GLUTINOUS RICE FLOUR

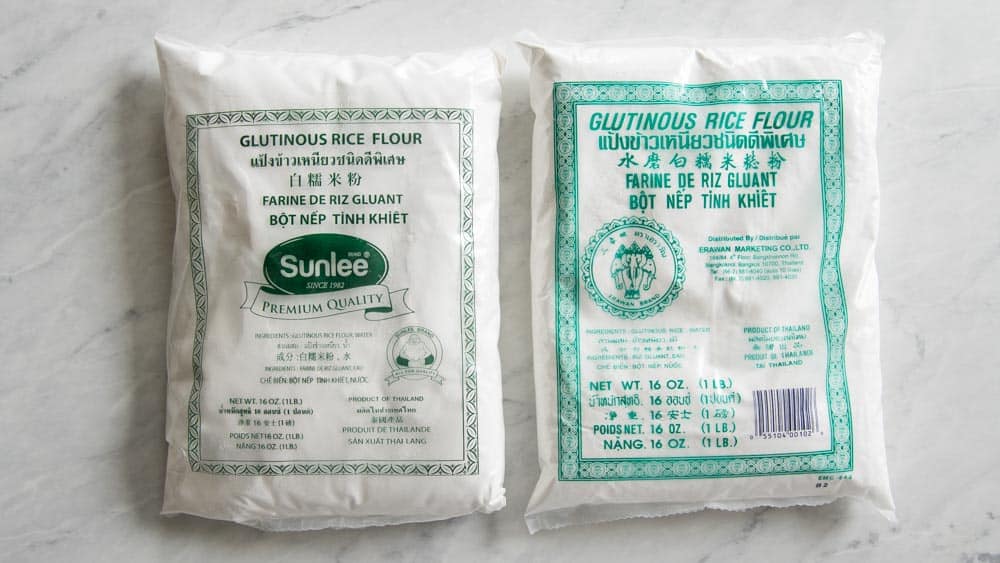

To make tang yuan, you must use glutinous rice flour. My mom typically uses Erawan brand’s glutinous rice flour (from Thailand), which comes in see-through plastic bags with a green label. You can find the flour in Asian grocery stores or on Amazon.

Do not use regular rice flour, as the rice balls will not turn chewy. If glutinous rice flour is difficult for you to find, you can try using sweet rice flour (such as Mochiko). Note that sweet rice flour/Mochiko tends to be a coarser grind compared to Thai-style glutinous rice flour, so the rice balls won’t be as silky soft.

MAKING TANG YUAN DOUGH WITH ROOM TEMP WATER

When Mama Lin started learning how to cook tang yuan, she made the dough with boiling hot water. Hot water turns glutinous rice flour into a very stretchy, pliable dough. If you ever make tang yuan with filling, you must make the dough with hot water so that you can easily manipulate the dough around the filling.

Because this style of savory tang yuan has no filling, you do not need to make the dough with hot boiling water. For the past decade or so, my mom has been using room temperature water to make the dough because it is a lot easier to handle. This “cold-water dough,” as my mom calls it, is much easier to knead and the dough doesn’t stick to your hands when you roll it into balls. Once cooked, the texture of the tang yuan made with hot water or cold water are about the same.

The drawback of the cold-water dough is that the raw rice balls can stick to each other or the plate they’re sitting on. As you roll out the balls and transfer them to a plate, make sure the balls don’t touch each other. When you are ready to drop the rice balls into the broth, invert the plate and gently brush them off. You’ll see that a tiny bit of dough will be stuck to the plate, but don’t stress about it. Mama Lin, ever the resourceful one, scrapes off and collects the dough to make one last tang yuan.

COOKING THE DAIKON

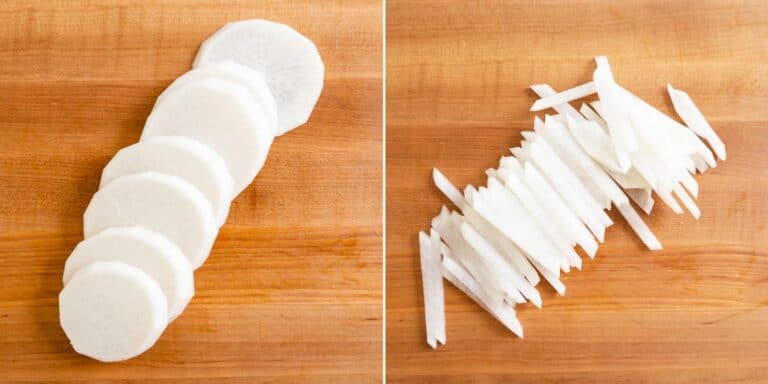

One key element to Mama Lin’s savory tang yuan is daikon (which we call 蘿蔔/萝卜, lo bak in Cantonese). Mama Lin prefers using what she calls “Chinese daikon,” which is long and plump versus “Japanese daikon,” which is long and thin. She claims that the Japanese variety of daikon is more bitter, though I can’t say I’ve noticed much difference.

To cook the daikon, she boils it with dried shrimp for umami flavor, as well as a small chunk of rock sugar (冰糖, bing tang). The sugar helps balance out the slight bitter flavors of daikon. Rock sugar can be difficult to find, so you can replace that with 2 teaspoons of sugar.

FISH PASTE

My mom always buys fish paste from a fishmonger in Chinatown or Asian supermarkets. In Sacramento, I’ve been able to find some at 99 Ranch Market. I like to add scallions to the fish paste to give them extra flavor. If fish paste is difficult to find, you can replace them with fish balls (found in frozen sections of Asian grocery stores) or Japanese-style fried fish cake (also found in Asian grocery stores).

CAN YOU MAKE THE TANG YUAN AHEAD?

Yes! Line a large plate with a sheet of parchment paper. Then, arrange the uncooked tang yuan over the lined plate, making sure the balls don’t touch each other. Once they harden, transfer the tang yuan to a freezer bag or container. I recommend defrosting the tang yuan before cooking them.

Savory Tang Yuan (鹹湯圓)

Ingredients

Glutinous Rice Balls

- 2 1/3 cups (250g) glutinous rice flour, use spoon-and-sweep method for volume measurement

- 1 cup (235mL) room temperature water

Daikon

- 1 medium daikon (about 550 to 600 grams), peeled

- 1 1/2 tablespoons oil, any neutral oil like vegetable, sunflower, etc.

- 3 cloves garlic, smashed

- 1/4 cup (15g) dried shrimp, rinsed

- 1 1/4 cups (295mL) water

- 1 small piece of rock sugar (about 8 grams), or 2 teaspoons granulated sugar

- 1/2 teaspoon Diamond Crystal kosher salt, or 1/4 teaspoon sea salt

Fish Cake

- 1 lb (454g) fish paste, from Asian grocery stores (see note 1)

- 3 tablespoons sliced scallions, optional

- oil for pan frying fish cake

Soup

- 2 tablespoons oil, any neutral oil like vegetable, canola, sunflower, etc.

- 1 large shallot, thinly sliced (about 3/4 cup)

- 2 links of Chinese sausages, sliced

- 3 cups (710mL) chicken broth, I used Better Than Bouillon low-sodium soup base

- 1/2 teaspoon Diamond Crystal kosher salt, or 1/4 teaspoon sea salt, plus more to taste

- 3 tablespoons sliced scallions

- 2 tablespoons chopped cilantro

Instructions

Make Glutinous Rice Balls

- Add the glutinous rice flour to a mixing bowl. Pour in 1 cup of water. Stir everything with chopsticks or a wooden spoon, until the water is absorbed into the flour. Gather the dough together with your hands and knead for a minute, until you get a smooth dough. The dough should feel like moist play-doh. If the dough is feeling very wet; add a few teaspoons of flour and knead again. If the dough is feeling dry, add a splash of water.

- Rip off about a small handful of flour and shape it into a log that’s about 3/4 to 1-inch thick in diameter. Tear off small pieces of dough that roughly looks like 1 ½ teaspoons per piece. This doesn’t have to be precise.

- Roll the small pieces of dough into small balls and transfer them to a large plate. Continue shaping the remaining dough into small rice balls. Set aside while you prepare the other ingredients.

Cook Daikon

- Trim off the green tops from the daikon. Slice the daikon into 1/4 to 1/2-inch thick slices. Then, stack the daikon slices and cut into strips (about 1/4-inch wide).

- Heat a large wok (or pot) with 1 1/2 tablespoons oil over high heat. Add the garlic and fry for about 30 seconds to 1 minute. Add the dried shrimp and cook for another 30 seconds to 1 minute. Next, add the daikon and 1 1/4 cups of water. Add the sugar and cover the wok with a lid and bring the water to a boil. Once boiled, reduce the heat slightly, and let the daikon simmer for 6 to 8 minutes, until tender.

- Uncover the wok and season with salt. (See note 2) Transfer the daikon and all the liquid to a bowl.

Cook Fish Cake

- Sometimes, store-bought fish cake paste can be rather plain. That’s why I like mixing sliced scallions into the fish paste. Feel free to leave out the scallions and skip straight to pan frying the fish cake.

- Brush a layer of oil over the back of a large, flat spatula (something like a wok spatula or a turner spatula). You’ll use the spatula to flatten and shape the fish paste inside the skillet. The oil helps prevent the fish paste from sticking to your spatula.

- Coat a large nonstick skillet with a thin layer of oil (about 1 1/2 tablespoons). Heat the pan over medium-high heat and add the fish paste. Then, use the greased spatula to spread and flatten the fish paste into a large cake, about 1/2-inch thick. Pan fry one side for 3 to 4 minutes, until golden. Use a large spatula to flip the fish cake over and pan fry the other side for another 2 minutes. Add a little more oil around the perimeter of the fish cake and tilt the pan around to distribute the oil.

- Transfer the cooked fish cake to a plate and let cool for a few minutes. Then, slice the fish cake into small strips (mine are usually about 1 1/2″ x 1/2″). Transfer the sliced fish cakes back to the plate.

Make Soup

- Heat the wok (or pot) with 2 tablespoons of oil over high heat. Add the sliced shallots and cook for about 1 minute. Add the sliced Chinese sausage and cook for 30 seconds more. Carefully pour in the chicken broth and drain the daikon cooking liquid into the wok. Cover the wok with a lid and bring the liquid to boil.

- Carefully transfer the rice balls into the wok. I usually invert the plate that’s holding the rice balls and use my fingers to gently brush off the balls. Cover the wok with a lid again and cook the rice balls for about 5 minutes. The rice balls should float to the top at this stage.

- Season the soup with salt to taste. Add the cooked daikon, shrimp, and fish cake to the wok and toss everything together. Turn off the heat and add the sliced scallions and cilantro and toss again.

- Serve the tang yuan in bowls with broth. Garnish with more scallions and cilantro, if you like. If you like a slight spicy kick, you can also add a dash of white pepper or chili flakes to the tang yuan.

Notes

- You can find fresh or frozen fish paste in Asian supermarkets. In Sacramento, I’ve been able to find fresh paste at 99 Ranch Market. I like to add scallions to the fish paste to give them extra flavor. If fish paste is difficult to find, you can replace them with fish balls (found in frozen sections of Asian grocery stores) or Japanese-style fried fish cake (also found in Asian grocery stores).

- My mom says that adding the salt too early will cause the daikon to turn slightly bitter.

- Freezing Directions: Line a large plate with a sheet of parchment paper. Then, arrange the uncooked tang yuan over the lined plate, making sure the balls don’t touch each other. Once they harden, transfer the tang yuan to a freezer bag or container. I recommend defrosting the tang yuan before cooking them.

Gloria says

Thank you so much! Much easier than I thought it would be but I made a few substitutions given what I had in the area. Being away from home during this time, I was missing this soup my aunt makes every Winter Solstice. This soup brought me home! 😢💗 It’s delicious and tastes almost like my aunt’s! I think if I used your ingredients it would be more like hers. I kept checking your posts and a few other people I follow HOPING you’d post a recipe and you then you did! Thank you, thank you, thank you!!!!

Lisa Lin says

Aw, THANK YOU GLORIA!! I’m so glad you found this recipe and made my dish! Glad it made you feel like being at home too because that’s exactly how I feel when I eat it.

Jason says

Love this recipe but I’m having trouble with the fish paste. I bought a “fish paste” from an Asian market and cooked it. The surface looked like your picture, but the cake itself had a scrambled-egglike texture and crumbled easily. Not sure if I bought the wrong one or cooked it wrong. Any tips?

Lisa Lin says

Hi, Jason! Oh no, sorry to hear the fish paste scrambled up! Was it fresh or frozen? Also, I just made fish paste from scratch for the first time, and I think if the wrong fish is used, or the paste isn’t gluey enough, it wont’ cook as smoothly. So, it could be the recipe of whomever made that fish paste.

Varnamala says

Delicious! The recipe ratios worked perfectly for me. Forming the tang yuan took some delicacy and perseverance but they came out great.